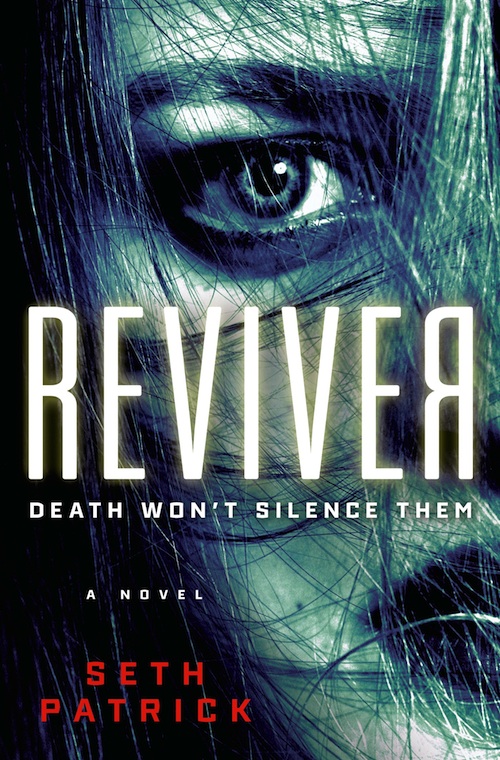

Take a look at Seth Patrick’s Reviver, out on June 18 from St. Martin’s Press and Tor UK:

Jonah Miller is a Reviver, able to temporarily revive the dead so they can say goodbye to their loved ones—or tell the police who killed them.

Jonah works in a department of forensics created specifically for Revivers, and he’s the best in the business. For every high-profile corpse pushing daisies, it’s Jonah’s job to find justice for them. But while reviving the victim of a brutal murder, he encounters a terrifying presence. Something is on the other side watching. Waiting. His superiors tell him it’s only in his mind, a product of stress. Jonah isn’t so certain.

Then Daniel Harker, the first journalist to bring revival to public attention, is murdered. Jonah finds himself getting dragged into the hunt for answers. Working with Harker’s daughter Annabel, he becomes determined to find those responsible and bring them to justice. Soon they uncover long-hidden truths that call into doubt everything Jonah stands for, and reveal a sinister force that threatens us all.

1

Sometimes Jonah Miller hated talking to the dead.

The woman’s ruined corpse lay against the far wall of the small office. The killer had moved her from the centre of the room; she had been dragged to the back wall and left propped up, slouched with her head lolled to one side.

Forensics had been and gone, leaving him to get what he could. They had been eager to leave. Jonah sympathized. Hearing the dead bear witness to their own demise was never pleasant.

He was wearing the standard white forensic coverall, as much to protect his own clothing as to prevent contamination of the scene. Gloves on his hands, covers over his trainers. He took a slow deep breath, ignoring the dull tang of blood in the air. It was a familiar smell.

The heavy wooden chair had been discarded next to the window, after the killer had used it to bludgeon the life out of the woman. Blood spatter was everywhere, clear swing patterns on the walls and ceiling.

The woman’s corpse had almost been pulped by the frenzied attack. Her limbs had been broken, her torso ripped and distorted, the back of her skull torn apart. However, the throat seemed undamaged; the lungs, from what could be seen of them, appeared intact. That was the important thing. Three cameras were placed around the room, ready to record everything that happened. It was vital to have the words spoken aloud.

The duty pathologist had not moved her. Disturbing the body would make revival more difficult, reducing the chance of success. Time of death had been estimated at around nine the previous evening, almost twelve hours before.

Her name was Alice Decker. She was a clinical psychologist, and this was her office; a family picture in a mangled frame lay on the floor, Decker smiling beside her husband and two teenage daughters.

With care, Jonah stepped around one tripod-mounted camera, his paper suit rustling as he tiptoed between cable and bloodstain. He knelt by Alice’s body and removed the latex glove from his right hand. Direct contact was an unpleasant necessity.

‘Everything ready?’ he asked, looking into the lens of the nearest camera. There was a brief confirmation in the earpiece he wore. The red indicators on the cameras went green as recording commenced.

Jonah took the victim’s shattered hand. ‘Revival of subject Alice Decker. J. P. Miller, duty reviver,’ he stated. He focused, the cameras recording in silence. Minutes passed. His eyes closed. His face betrayed nothing of his work’s difficulty, but it was this part that he hated most, this plunge into the dark rot to bring his subject back.

A violent death was harder, and Jonah was always dealing with violent deaths.

The violence also limited the time he would have. When he brought Alice back, he expected five minutes of questioning at most, perhaps far less. He would release her as quickly as he could, once there was nothing more to be learned. After the indignation of death, and the sacrilege of resurrection, it was the least he could do.

He opened his eyes and breathed deeply. He’d been going for twelve minutes and was close to success, the worst of it over, but he needed a moment to prepare for the final effort.

Her open eyelids flickered, an early indication. For a moment, his gaze stayed on her left eye, which had been punctured in the attack and had spilled slightly onto her cheek, leaving the eyeball surface subtly wrinkled. The tip of the bone shard that had caused the wound was visible in the fractured mess surrounding the eye, retreated now that the damage was done.

Above her left ear he saw a flap of Alice’s scalp that had been lifted in the assault. The severe damage underneath was a confusion of colour – whites, greys and reds mingled with Alice’s blonde hair. The worst of the damage to the head was at the back, pressed to the wall and not visible.

Ready at last, Jonah closed his eyes and continued with the revival. Moments later, her throat quivered briefly. A dozen more seconds passed, and then he had her.

‘She’s here,’ he said.

The corpse inhaled, an unpleasant wet rasping coming from the chest. Jonah couldn’t help noticing how unevenly the chest rose, open in places, jagged lines clear through clothing. Low cracks of bone and gristle were audible under the groan of air entering the dead woman’s lungs. Her vocal cords started to move, creating a gentle wail.

Full, her chest halted.

‘My name is Jonah Miller. Can you tell me who you are?’ Jonah tensed, waiting. It was far from certain that she would be able to respond at all, let alone audibly.

A low sigh rose from her, the grim bubbling from her lungs distressingly loud in comparison.

Then a word formed. ‘Yesss…’ she said. ‘Alice…’

To the cameras, her voice was a whisper, monotone and distant. To Jonah, it was as if the corpse spoke directly into his ears, with a terrible clarity. This clarity was equally true of the emotional state of the subject, laid bare to the reviver. With murder, the emotion was often anger. Anger at being dead. Anger at being disturbed.

Gripping her hand, Jonah leaned in. He steeled himself and made full eye contact. The dead couldn’t see, but if he avoided looking his subject in the eye, he felt like a coward.

‘You’re safe, Alice,’ he said. His voice was calm and warm.

The chest fell as Alice exhaled. Sounds of popping, and of tissue coming unstuck, came from her. She inhaled again.

‘No…’ she said. Her voice was full of despair, and this was a bad sign. He needed indignation, not self-pity.

He paused, uncertain whether she was aware of her situation. It was more common in adult subjects; sometimes they simply didn’t know they were dead. A refusal to accept it could bring the revival to an abrupt end, a rapid onset of incoherence, then silence.

‘Do you know where you are, Alice?’ he asked.

‘My office.’ Her tone, her sense of loss. He could tell: she knew what had happened, and was understandably afraid.

‘Please, let me go,’ she said. Jonah halted, a painful memory surfacing. He had heard those words often enough since, but they still made him pause.

‘I will, but there are questions I have to ask. What happened here, Alice? What happened to you?’

Alice exhaled, but said nothing. Precious seconds slipped past. Jonah knew how agitated the observers would be, watching their key witness flounder, knowing time was short, but he was patient. At last, the chest moved again, and she inhaled.

‘Please, let me go,’ she said.

Jonah considered his options for a moment, then chose another tack. He made his voice cold, stern.

‘Tell me what happened, Alice. Then I’ll let you go.’

Another pause.

‘We want to catch who did this, but you need to help me.’

Still no reply. He decided to risk scolding her.

‘Don’t you care what’s been done to you?’

He sensed anger forming, outrage congealing from her despair.

‘I was alone,’ she said. ‘The building was empty. I was working. The door opened.’ She inhaled, then paused. With each breath she took, with each pause she had now, there was a risk of it being a final silence. He needed her to keep talking, her breaths momentary delays. Time was running out.

Yet he had to take care, not push too hard. He waited a few seconds before prompting. ‘What time was it?’

‘Eleven. Just after. I asked him what he was doing here.’

‘Who was it, Alice?’

‘He said George had let him in but George had gone hours ago.’

‘Who was it, Alice?’

‘He’d been crying, I could tell; blood on his hand, he saw me notice and hid it behind his back.’

‘Who was the man, Alice?’ He was anxious to get the name, in case she stopped. The details could wait.

‘I said something about the door, to distract him. He looked away, and I tried to use the phone. I knew I was in trouble.’

She stopped, not inhaling this time.

‘Who was the man, Alice? What’s his name?’ He heard one of the observers swear, and felt like doing so himself. Then Alice inhaled again, more deeply than before. Her back slid several inches along the wall, making Jonah flinch.

Reluctant, he moved closer, and reached around with his right arm to cradle her. He pushed his knee hard against her legs, supporting her enough to prevent her slipping out from the wall. He was brutally aware of her injuries now. A splinter of rib dug painfully into his forearm. He could feel her breath on his face as she spoke.

‘He saw my hand on the phone. He moved fast, and wrenched it off the table. He hit me hard, the side of my head. I fell. He picked me up – threw me. The rage on his face, I asked him please, please.’ And then, to Jonah: ‘Please, let me go.’ She stopped again.

‘What was his name, Alice? His name.’

Jonah found himself holding his breath. Fifteen seconds passed. With a suddenness that made him start, she inhaled; he could feel the muscle tear, feel the bones grinding against each other.

‘Roach,’ she said, her voice fading now. She was losing focus, dissipating. ‘Franklin Roach. He lifted the chair. I saw him swing it at my head. So much rage.’

Silence. His intuition told him there would be nothing else. Jonah waited a few moments before speaking to a camera.

‘I think that’s all we get.’

He got a confirmation that it was enough, and then the green camera lights went red as recording stopped.

He turned back to Alice. Silent as she was, she was still present. Release would come the moment he broke physical contact – the moment he let go of her hand.

‘We’ll catch him.’ His voice was tender again. ‘You can rest now.’ He was about to release her when she spoke, a terror and an urgency in her voice.

‘Something’s coming,’ she said. ‘Please, let me go. There’s something coming.’

She was confused. Somehow, she had refocused, and Jonah was reluctant to let her go like this. He wanted to reassure her. The terror she was feeling was considerable, and Jonah had to work hard to keep calm; revivers sensed the emotions of the subject, and as those emotions grew stronger they could prove overwhelming.

‘There’s nothing coming, Alice. You can rest now. It’s over. You can sleep.’

‘Something’s coming … please, let me go!’

‘Alice, it’s OK, it’s OK. You’re safe.’

‘I can’t see it! I can’t see it!’ Her lips barely moved, her voice fading, but to Jonah she was screaming.

‘Alice, you’re safe. Please, you’re—’

‘It’s below me!’ The fear surged, sudden and total. He was frozen now, bewildered and infected by her level of terror. He had an image of darkness beneath him, stalking, circling. ‘Please, please, let me go! Please, it’s…’

Jonah released her hand and lurched away from her. He scrambled back, staring, appalled that his inaction had led to such distress. She had simply been confused; her words were meaningless. He should have let her go at once.

And yet. It hadn’t just been a desire to reassure her that had made him delay. He had felt something. He turned to a camera.

‘Did you get any of that?’ he asked, but there was no response. Nobody was watching. Then the red light on the camera faded and died. Jonah looked at it, puzzled, and saw movement reflected in the blank lens. Movement behind him. He turned back to the corpse. Alice’s head, which had been lolled to one side for the duration of the revival, now twitched and rose. The eyes moved to look at him.

It wasn’t Alice. Jonah had no idea what this thing was, staring back at him. It spoke.

‘We see you,’ it said, and then it was gone.

2

The knock on Daniel Harker’s door came just after half past one.

The afternoon was hot and muggy. Daniel had been out of bed for only an hour, and wasn’t in the mood for visitors. He’d heard the car tyres crunching on the gravel out front, and the footsteps approach his door. When the knock came he’d already decided what to do. He ignored it.

He sat alone in his kitchen, curtains still closed, eating a bland lunch of dry toast and tomato soup. It was all he could stomach. He looked at the two empty wine bottles on his sink drainer and vowed not to drink for several days. Or until evening, at least.

He knew he was drinking too much, but it was an annual pattern. Each year, the hated month of April would arrive. Each year, he would become withdrawn and uncommunicative, sinking into a depression that would have a tight hold until the end of June.

June was more than half gone now, and his daughter Annabel was coming home for the Fourth of July; home from her own career as a journalist in England.

He needed a week to straighten himself and the house out, make it presentable and welcoming. She knew about his dark times, certainly. She had as much of a share in them as he did, but she was young. She had her own way of dealing with things.

Her annual visit marked the end of Daniel’s grief, at least until the following year. It gave him a deadline, something he always needed to focus his mind. Without her coming, he suspected he would rough it indefinitely. He knew his daughter thought the same. And every year, she gave him just long enough, and no more. Every year since her mother’s death.

He missed Robin. God, he missed his wife.

She had been an elementary school teacher and had loved what she did, continuing to work even after Daniel’s wealth and success had arrived.

‘We’re rich,’ he told her time and again. ‘We should be living it up, making the most of it.’ Robin’s answer was simple, and it shut Daniel’s mouth at once. She would give up her job, if he gave up writing. And that wasn’t something he would consider.

But it had not been his novels that had brought their wealth.

After leaving university with a degree in English literature, he had drifted, taking a year-long journalism course both to delay the need to find real work, and to give him a career he could use as backup while he toiled away on his novel.

Yet that book died, and he began another. He found work, meandering from newspaper to magazine, and earned a reasonable wage with a competence and dedication that made him a respected underachiever.

His pieces were well-crafted and punctual, but he lacked the luck and judgment of some of his peers. He lacked something else as well – the ability to spin, to distort, to lie, and expand the smallest nugget of truth into something bigger. So he broke underwhelming stories while his novel writing stuttered and failed.

But then, twelve years ago, he discovered Eleanor Preston. He found the first reviver.

* * *

A friend had passed a possible lead his way: a claim of a fraudulent medium, stealing from the bereaved.

Sixty-year-old Eleanor Preston had worked as an administrator in a hospice for twenty years, until Trudy Brewer’s interference got her fired. Brewer’s uncle had died at the hospice; Eleanor Preston had then, according to Brewer, offered her services to Brewer’s parents for a significant payment. Daniel’s first impressions of Trudy Brewer weren’t positive. Her real concern seemed to be financial: her uncle and parents were relatively well off, and Daniel could see that any payment to Eleanor Preston would be coming out of Trudy Brewer’s inheritance.

When Daniel spoke to her parents, the situation seemed innocent enough. They were coy about what Eleanor Preston had actually done for them, but they assured him that Preston had taken no payment. Daniel’s interest waned, with the prospect of a meaty story – something he could actually sell – dwindling, but they had already arranged a meeting that Daniel felt obliged to accept.

‘I didn’t know what happened, the first time,’ Eleanor Preston told him. The two of them were sitting on a bench in a park five minutes from her home. The sun was low, the November air cold. Daniel was hoping to be gone before dusk fell.

A little overweight and with a smile ingrained in her face, Preston was likeable. He felt sorry to be wasting her time.

‘This was just shy of a year ago,’ she continued. ‘Maggie. A lonely woman, seventy-three. What was left of her family had made sure she was comfortable in the hospice, but hardly came to see her. I was in the habit of spending any spare time I had talking to those who were left alone more than I thought right, and for a few weeks I spent that time with her. I was the only one would see her through to the end, and we both knew it. It would be another two or three weeks, I thought, but one morning between early rounds and breakfast she died. They let me sit with her once she’d been pronounced. Left me alone with her awhile. I took her hand and told her I was sorry I didn’t get to say good-bye. I didn’t understand what I did next. Still don’t, not really.’

Daniel shifted on the bench, the cold working its way through him. He rubbed his hands to warm them. He noticed Eleanor Preston’s look, and tried to keep his impatience out of his voice when he spoke. ‘So until a year ago, you didn’t know you were a medium?’

Eleanor smiled. ‘Oh, I’m no medium, Mr Harker. Quite honestly, I don’t know what I am. I’ve helped five families since then. I take no money. And I knew it was just a matter of time before it all came out. But I’m no medium.’

Daniel asked what she meant, and Eleanor Preston told him every last ridiculous detail. The dead spoke to her, she explained. Physically spoke. Not a medium, Daniel thought. Not even a con-woman. Just crazy. The disbelief was written on his face, he knew, but Preston continued, watching him with a look of amused tolerance. She told him of another ‘session’ she would be doing the next night, one which the family was willing to let him observe and record.

She believes this, Daniel thought. He wanted to understand how an apparently rational woman could have deluded herself so badly. Perhaps that could be his story.

And so, thirty hours later, Daniel went to a funeral home with Eleanor Preston. In a small private room, a dead man lay on white sheets. The only others present were the man’s wife and daughter. They greeted Daniel with such warmth that he felt his cheeks burn, knowing they were as deluded as Preston.

He was asked to take a seat, and he did. After fifteen minutes, he believed. Five days later, so did the rest of the world.

* * *

There was another knock on Daniel’s front door. Why the hell they were being so persistent he didn’t know, but he didn’t feel like speaking to anybody. He’d only been out of the house twice in the past five weeks, barely managing to overcome his desperate need for solitude, and for what? The man he’d gone to meet hadn’t even shown up the second time.

Whoever it was at the door could leave a damn note and let him alone. He took his plate to the sink and washed up.

Behind the sink, hung on the wall, were two framed covers that had transformed his life. First, the cover of Time, a modified reprint of the article he had written in a fugue twelve years before. ‘Speaking to the Dead,’ the title read, his name below it.

Beside it, the cover of his first published book, the source of his wealth – his, and Eleanor’s too. It was in part an account of Eleanor’s life, but the main focus was the Revival Baseline Research Group, the research effort that had been established in a blaze of public interest to investigate this new phenomenon.

He liked to look at those covers, because he was proud of what he’d written and the reaction his work had prompted – one of fascination, not fear.

Standing in Eleanor Preston’s spare bedroom with a speaking corpse, Daniel had stared, frozen, trying to understand just how Eleanor could have faked such a thing. But the truth of it was undeniable, almost visceral; his cynicism was dispelled with each word that came from those dead lips. For a moment, he had been consumed with horror – knowing it was true, and terrified of what was to come. But as Eleanor Preston had spoken, prompting the dead man with gentle questions, Daniel’s fears vanished, the atmosphere calming and softening as the deceased spoke to his family.

The exchanges were tender, personal. The man spoke of times he remembered, times he cherished; he made his wife and daughter promise to live their lives fully, and remember him with a smile. His family, in tears, repeated ‘I love you’ and ‘I miss you.’

They said their good-byes, and were joyful.

Daniel’s article had captured that moment.

* * *

The world reacted as it always does to the great truths. First, with ridicule; then, hostility; and finally, acceptance. The ridicule lasted for days after the story broke, but it faded faster than Daniel had expected. The footage he had taken retained much of the power he had felt that day, and accusations of forgery rang false to most of those who watched it. Those who declared it a hoax sounded more and more uncertain. When Eleanor Preston repeated the feat under close scrutiny, the world made up its mind. Revival was real.

Anger and fear followed. It was denounced by many as an abomination. Some of that anger found its way to Daniel. The fact that he had broken the story gave him some authority, but also part of the blame. Threats came by letter, by email, by phone; it was a difficult time. Eleanor fared less well, and Daniel watched on, feeling for her as she was put in hiding for her safety, her home gutted by arson.

It would have been so easy for the world to have turned against revival, but the rage subsided. In part, Daniel thought, it was due to the tone of his articles. Other journalists later focused on the macabre elements and played up the unease. Daniel always went the other way. Here was something new, he had said in that first article. Something that, in this case at least, was undeniably good.

Yet he knew the main reason for the anger dissipating was simple, and very human. Revival was evidence of a life essence that survived death. Different faiths interpreted the effect in their own ways, but any hint of evidence of an afterlife was embraced.

The angry rejections of revival were far outnumbered by those who wanted to know what it meant.

* * *

Eleanor Preston refused to deal with the media, except through Daniel. He would write her biography, and they would split the profits. She had plans for the money, she told him.

The government set up an investigative group to examine Eleanor’s claims. She was wary; her only desire was to prove to the remaining sceptics that revival was real, and to get back to doing what she wanted to do – let the dead say good-bye and the living heal.

She agreed to the investigation, but with restrictions. She would only conduct revivals for the grieving. Everything the researchers wanted would have to be tailored to that: nonintrusive, respectful.

With agreement reached, the Revival Baseline Research Group was formed. It became known as Baseline. There was no shortage of scientists interested; funding was both American and international, governmental and private.

It was quickly established, beyond doubt, that revival was a genuine phenomenon.

Eleanor had always believed that revival was something new, and that more would have the same skill she had. She was proved right. People came forward; those who recognized part of themselves in Eleanor’s descriptions of how she felt; those who experienced the feeling of cold when they touched people, a feeling that revivers would soon label ‘chill.’ Finding other revivers, who would not be bound by Eleanor’s restrictions, was crucial to Baseline’s investigations. And while most failed the ultimate test of an actual revival, some succeeded.

Eleanor left Baseline in their hands. Three months after being revealed to the world, the first reviver went back to her calling. Later, after the overwhelming success of Daniel’s book, she used her money to set up the first private revival service, launching an industry that even became a common, if expensive, insurance option.

The world, meanwhile, waited for news from Baseline. Waited to find the ultimate truths they sought. What was the nature of revival? Why had it started to happen? What did it mean?

They would be disappointed.

Some discoveries were made, of course.

Eleanor’s revivals had not been representative of the true success rate; revival after death from natural causes was much easier than after one involving physical injury.

It was not simply the brain being woken – severe head injuries made revival more difficult, yes, but not impossible, and the subjects were lucid, the damage to the brain irrelevant once revival was achieved.

There seemed to be no electrical activity at all, either in the brain or in the muscles that moved the lungs and vocal cords. However, the source of the movement could not be identified.

By the end of its first year Baseline had a stable of twelve revivers, and became focused more on the details of successful revival – how to make success more likely, how to extend its length – and less on what revival itself was.

What hostility remained gradually coalesced into a protest group called the Afterlifers, well funded from an uneasy collaboration of disparate religious interests who saw revival as desecration, an unacceptable disturbance of the dead. But loud as they were, they found their calls for a moratorium ignored. Direct action from more extreme members brought public disapproval. Their message of outright objection to revival took a backseat, replaced by more successful calls for greater control, rights for the dead, and a system ensuring revivers were licensed.

For many, Baseline was a failure. Even with its count of revivers increasing, with over one hundred revivers out of a worldwide tally of almost three hundred, it would get no closer to the mystery of where revival came from; find no smoking gun for anyone’s preferred God.

Baseline would continue for another five years before being disbanded, public funding drying up as the certainty of discovery faded, transforming into an expectation that the truth would always be elusive. Many lines of research were discarded; some of the companies who had contributed brought teams back to their own facilities to continue, but it was the potential for profit in the burgeoning fields of both private and forensic revival that guided their work now, not the search for meaning.

For Daniel, with financial security beyond anything he’d expected, it was a new beginning. He and Robin bought a perfect home; he began to write fiction again, insisting on a pseudonym for his crime novels to see if they had wings of their own. Later, as forensic revival became accepted, he started the Revival Casebook series under his own name, case histories from real revivals with sensationalism kept to a minimum. He even took an executive producer role on the inevitable TV series until they started to take too many liberties with the truth.

He was busy. He was happy. For a time.

* * *

He heard a sound from the hall – a man calling his name from the front door, and another burst of knocking. For Christ’s sake, leave a card and go, he thought, sitting back down at the kitchen table. Then he cursed again, annoyed with himself and his annual withdrawal from the world, his difficulty in breaking it.

Hanging on the wall to his left were two framed photographs. The larger of the two showed him and Robin, with a fifteen-year-old Annabel, on Myrtle Beach. He thought back to the camera, balanced precariously on a rock, himself running back to his family before the timer counted down. The image was his favourite of all their family pictures. Informal, a warm, natural smile on all three faces; taken two years after Preston’s discovery, as his second crime novel was released and well reviewed.

Ten years ago, probably the happiest time of his life. Four years before Robin died.

He thought of the first time they met. He thought of her smile, the first thing he’d seen of her; of her accent, a soft English forged from a childhood first in Yorkshire in the north of England, and then Sussex in the south. It was an accent she would never lose.

‘You came to America to do English. What the hell for?’ he asked her. She was taking an English degree, but she’d chosen to come halfway around the world to do it. He hadn’t meant to be cruel, but her face had fallen.

He’d sworn to himself to do what he could to make that smile return.

They married three years later, and it was good. Even with the financial pressures, and Daniel’s frustration at his underwhelming career. Neither of them had close family; both were only children, with no surviving parents. It intensified what they meant to each other. When Annabel was born, despite money becoming even tighter, Daniel felt blessed. He also felt anxious, waiting for the bad luck that he seemed to have evaded since meeting his wife to finally track him down. When at last the money came, he thought his life was perfect.

* * *

Then one April, out of nowhere, Robin collapsed at work. She was dead by the time Daniel had reached the hospital. A brain hemorrhage.

His heart had been torn out, and he had not recovered. She had been part of his core, part of what made him who he was, and she was gone. Now six years had passed, and his grief for Robin was as sharp-edged and barbed as it had been on the day of her death.

Annabel had kept him alive. She was in her first year at university in England, and had returned immediately to find her father destroyed, barely able to talk. Robin had always planned for a private revival in the event of her death, but when the time came it proved too difficult for Daniel. He stayed away and left Annabel to attend alone. It was not something he ever expected Annabel to forgive him for, just as he would never forgive himself. Self-hatred swamped him over the following weeks; trapped in his despair, withdrawing from his life, from his own daughter.

Robin had been stronger than him, always, and Annabel had her mother’s strength. Even though he was angry and uncommunicative, Annabel stayed with him for five months, putting her university studies on hold. When he eventually emerged from his despair, their relationship had changed; but damaged as it was, Annabel had not allowed it to wither, even as the pattern repeated.

For Annabel, April would always be her mother’s death, but it was also the time her father grew dark and distant. He knew his behaviour made it so much worse for her, but every year – every April – Daniel found himself plummeting, whatever he tried to do to distract himself. Unable to work, drinking heavily, alienating his daughter once again. And yet, always coming back.

She would be home soon. It was time, Daniel told himself, to once more call an end to the grieving. It was time to live up to Robin’s memory, rather than collapse under the weight of loss.

It was a realization that came every year, but it was always hard-won. It marked the rebirth of his own life. Annabel – his little Annie – would be here soon enough, and he would smile and laugh with her, and repair what they had, and be happy again.

There was another knock at the door. He glanced at his watch. Whoever it was had been trying for ten minutes now, while he’d been ignoring them. Hiding from them, as he’d hidden from life for the past few months. Enough hiding, he thought, and stood.

Resolved to face the world, Daniel Harker walked to his front door and opened it. His body would be found twenty-five days later.

From Reviver by Seth Patrick. Copyright © 2013 and reprinted by permission of St Martin’s Press, Thomas Dunne Books.